This article originally appeared in Crisis Magazine, February 26, 2018. See it here

The 50th anniversary of the Kerner Commission report, which famously noted: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal,” comes during a year filled with anxiety and consternation. After the 2016 presidential election, outrage — instead of hope and change — inspired a new resistance against inequality and discrimination. Many believed we had seen the end of White supremacy in the Obama years only to realize the intractability of racial apartheid and the persistence of White privilege.

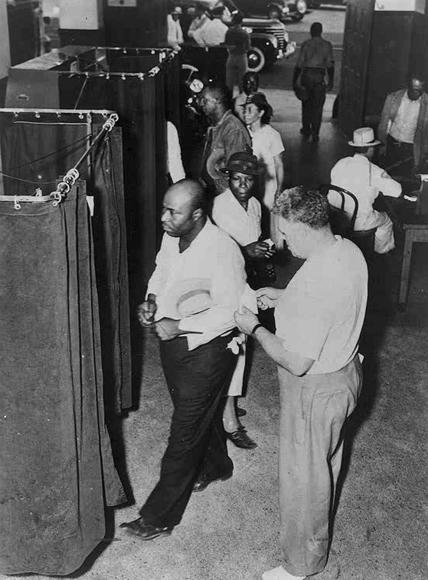

The Kerner Report was a search for answers after years of deadly unrest in the nation’s inner cities. In the summer of 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders in response to riots sparked by police abuse. He sought to show leadership in restoring order. Rioters called their actions rebellions against a long train of police harassment and violence. Though disturbances had occurred before the 1960s, they took on new meaning in the context of the gains of the Civil Rights Movement. The disorders had become endemic beginning with Harlem; Jersey City, N.J.; and Philadelphia in 1964, Los Angeles’ Watts area in 1965, in 43 cities in the summer of 1966, and then the explosions in Detroit and Newark, N.J., in 1967.

President Johnson expected the Commission, known by the name of its chairman Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner and with NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins among its members, to investigate FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s claim that the riots arose from communist plots. Surprisingly, given the moderate backgrounds of the members, the Commission’s report, released on Feb. 29, 1968, reached beyond the surface. The members identified the same persistent conflict in police-community relations, and the underlying causes of poverty and discrimination that federal and local commissions had been emphasizing for years. The commissioners concluded their report by asking the nation to make the eradication of poverty, joblessness and racism an urgent priority.

The Kerner Commission worked in what otherwise seemed auspicious times. The Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had marked major race relations change. Johnson’s War on Poverty and community action agencies included decision-making by the poor. The economy seemed sound, and the Vietnam War had not yet drained the budget. But the period also saw increasing resistance to police brutality, the rise of the Black Panthers and Black nationalist movements. The report was issued more than a month before the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., which set off more riots in the United States and even abroad.

Underscoring a “system of failure and frustration that dominated the ghetto and weakened society,” the Commission recommended the development of programs in education, housing and jobs on a scale equal to the dimensions of the problems. It emphasized the need to make better quality education available to Black children and more housing available for low-income people. The panel asked for local government responses to the accumulated grievances of Blacks that had been ignored. It encouraged the recruitment of more Black police officers and strategies for improving police community relations, so that the police would not be regarded as an occupying force.

The Commission also noted a need for greater financial benefits and more flexibility in the distribution of public assistance to the poor.

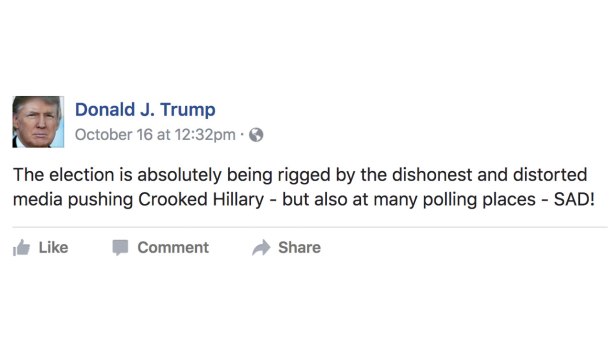

The Kerner Report lamented “fake news,” pointing out that the news media did not effectively communicate what was actually happening in Black neighborhoods. Therefore, the Commission recommended regular coverage and the recruitment of more Black journalists.

President Johnson barely acknowledged the Kerner Report. He thought he was not given sufficient credit for his Great Society programs and refused to endorse the demand for a large deployment of financial resources to solve the problems identified. Some historians believe he worried that the report’s emphasis on the responsibility of White racism for the inequities Blacks faced would impact the Democratic Party’s electoral prospects.

Despite Johnson’s reluctance, the media, as one example, announced programs to become more diverse in their staffs and reporting. Progress was so hard to come by, however, that in a 1977 Window Dressing on the Set report the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights lamented the slow pace of change in the media.

In the years since the Kerner Commission, the slight progress for some Black Americans pales in comparison with the dire conditions of the poor and working class. There have been CEOs of major corporations, several African-American governors, several U.S. senators and of course Barack Hussein Obama’s presidential election and re-election. But according to Pew research, the wealth gap between Black and White households has widened since 1983. There is a Black wealth gap, too: for every Oprah Winfrey, LeBron James and Richard Parsons, there are far more impoverished and imprisoned Black people. There is a Black reality gap. Most middle-class Blacks are disconnected from the lives of the needy. They live in areas far removed from the reality of life in poor Black neighborhoods.

Incarceration rates because of drug addiction and offenses have devastated Black families. Congress and President Johnson started the distribution of large amounts of federal money to police departments under the Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, the same year of the Kerner Report. Thereafter, President Richard Nixon’s war on drugs pushed mandatory sentencing, no-knock arrests and increases in the local activities of federal enforcement agencies. Administrations since have continued the pattern often with the approval of local Black politicians. Hillary Clinton was severely criticized during the 2016 campaign for President Bill Clinton’s role in mass incarceration and calling young Blacks “super predators.”

The Kerner Commission’s famous opening description: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal,” remains a touchstone. Even as our society has diversified, the Black-White divide remains. The Kerner Commission correctly noted and expected poor Blacks would become increasingly concentrated in major cities. But the Commission did not anticipate the war on drugs, militarized police enforcement, mass incarceration and persistent poverty, which cleared Blacks from urban neighborhoods to make way for White gentrifiers. The failure to rebuild riot-torn neighborhoods made gentrification easier. This process, controlled by Whites and enabled by mayors and other Black elected officials, did not ensure housing and necessary programs. This pushed poor Blacks into homelessness or the inner ring of suburbs. Even well-off Blacks now reside mostly in segregated communities.

But there is hope.

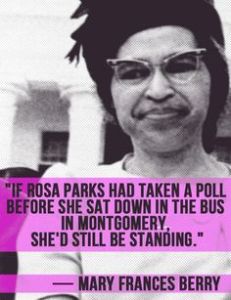

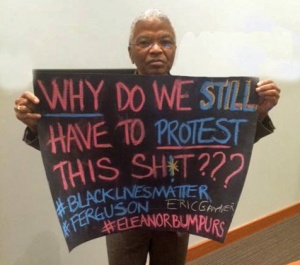

In July 2013, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Opal Tometi founded Black Lives Matter after the killing of Trayvon Martin. The deaths of Michael Brown, Kayla Moore and other unarmed Black men and women may have gone unnoticed if it were not for the group’s rallying cry. Their protests and campaigns against police violence had won minimal concessions from politicians and law enforcement. Most of the group’s demands remained unmet. In August 2016 during the run-up to the election, Black Lives Matter and other anti-racist organizations formed the Movement for Black Lives (MBL) and issued a platform that challenged candidates to commit to progressive policies. The platform is one way to assess the work that must be done 50 years after the Kerner Report.

MBL’s platform addressed issues such as education, health care, jobs and police-community relations. These were issues that the Kerner Commission addressed 48 years earlier. But the platform also sought reparations for slavery, long endorsed by the NAACP. It envisions the abolition of zero-tolerance policies and the policing of schools, which are disproportionately used to punish Black children. Black boys and girls especially are suspended from school and disciplined and ushered into the school-to-prison pipeline.

In keeping with the Movement for Black Lives’ diverse coalition, its platform called for an end to LGBTQ discrimination and, specifically, a demand to end the killings of Black and Latina transgender women. The Kerner Commission’s attention to immigration consisted of explaining why Blacks experienced more employment, education and housing discrimination than earlier White European immigrants. Sex and gender violence as community problems went unmentioned because they were not considered racial matters.

The Kerner Commission’s two separate societies rubric failed to stimulate the change needed. It could have been used to inspire progress but was hollowed out as the will for change dissipated. Today’s activists, as reflected in the Movement for Black Lives’ platform, believe that a multi-faceted coalition of the marginalized might achieve progressive change more effectively. Yet the racism experienced by Blacks descended from those enslaved in the United States is not like the discrimination experienced by other people of color. Its causes, history and effects are different, and remedies must fit the facts.

The Kerner Commission report’s depiction of the many persistent problems Blacks faced in 1967 remains accurate 50 years later. The Movement for Black Lives’ platform seeks to change the narrative. Two of its criminal justice demands received an almost immediate successful response. The MBL platform’s demand to stop punishing poor people with fines beyond their means to pay for minor offenses arose from the protests in response to the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. The practice of Ferguson and other municipalities of raising most of city operating funds through traffic fines drew wide public notice. Police targeted African American drivers for mostly minor infractions in numbers that far exceeded their population. Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder called this practice “revenue generation through policing.” The Obama Justice Department urged state chief judges and court administrators in states to end punishing and imprisoning poor people with fines and debts they cannot pay. However, Attorney General Jeff Sessions withdrew this guidance to the states.

The platform demand to end using criminal history in job applications had some success. The Ban the Box campaign persuaded 100 cities and counties, 18 states and federal employers to leave background checks for late in the hiring process, after an applicant has been able to show qualifications for the job opening.

The Kerner Commission did not address police sexual abuse of Black women and girls in Detroit and other cities as a source of the anger that helped to fuel women’s participation in the riots. This was a #MeToo moment long before the #MeToo movement. Since the Kerner Report and even the recent platform of the Movement for Black Lives, sexual harassment has become a major issue — for not only the movie stars and professional women harmed, but also poor and working-class women in minimum-wage jobs. Police sexual assault of Black women under surveillance or arrest also remains a problem.

The Kerner Commission concluded that the perpetuation of inequality and injustice —and not communists — caused racial unrest. Its conclusion has been reiterated by numerous reports and government studies since. Sadly, the most consistent policy result of riot reports has been increased funding and authority granted to local police agencies. Some of the major beneficiaries have been the real estate developers of today building in urban areas. Protests have been responsible for the miniscule positive change that has occurred. As I have often said, protest is an essential ingredient of politics. History teaches us that resistance works. But it must be targeted, persistent and strategic. Let us organize in local communities to do the work that must be done so that the Kerner Commission report becomes someday nothing more than an identification of problems long past.