The time when you need to do something is when no one else is willing to do it, when people are saying it can’t be done.

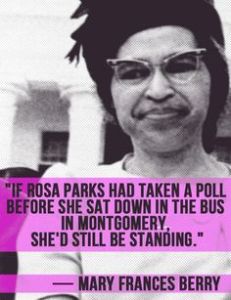

If Rosa Parks had taken a poll before she sat down in the bus in Montgomery, she’d still be standing.

Racial tensions are a major problem in the states in which the church burnings took place.

Stereotyped by the media, ignored by politicians, young poor black males face almost insurmountable obstacles to fulfilling the American dream.

Everywhere, African-Americans are stopped far out of their proportion in any of the communities policed.

When you have police officers who abuse citizens, you erode public confidence in law enforcement. That makes the job of good police officers unsafe.

Civil rights opened the windows. When you open the windows, it does not mean that everybody will get through. We must create our own opportunities

.

Tag Archives: Voting Rights

Power to the People: Why We Need Police Civilian Review Boards

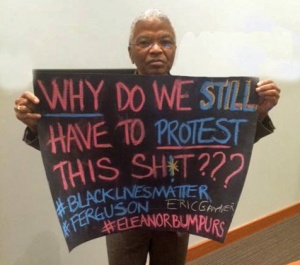

As distasteful as it is to anticipate the next shooting of an unarmed African American by law enforcement officers, it’s also sadly inevitable. When it happens next, government officials and the media will attempt to diffuse the righteous anger on display in the community protests just they have done before in demonstrations against the killings in Ferguson, Missouri, in New York City, in Los Angeles, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and elsewhere. The mayor and the police commissioner will suggest that “justice” will be served and the murderous officer prosecuted. But justice rarely arrives despite videos and testimony.

Indictments of law enforcement are almost impossible to obtain for three very simple reasons. First, local District Attorneys are elected officials and voters (whites and even many voters of color) are ambivalent about curbing police power. Second, prosecutors do not want to antagonize the law enforcement agencies they depend on to do their jobs. Law and order protect each other.

Third and most troubling, federal civil rights law requires that to successfully prosecute a police officer for such crimes, “intent” must be proven. In such cases, the “smoking gun” and videos don’t matter, motive does. The prosecutor must show that the officer intended to kill the victim and that he fired on the victim due to racial animus. (Which is why police were so upset when “Anonymous” outed some law enforcement officers in the Ferguson area as members of the Ku Klux Klan.) Civil suits filed by family members against police departments for “wrongful death” tend to be more successful because they don’t need to prove Officer JQ Public was racially motivated.

This is one of the tough issues that organizers of #BlackLivesMatter, Million Hoodies Movement for Justice and local community groups, as well as the established national civil rights organizations must confront. For years, activists have lobbied on Capitol Hill to amend the federal statute with support from the Congressional Black Caucus, but law enforcement representatives wield greater power. With change in Congress difficult to achieve, focusing on local governments and local officials can build the necessary political pressure and develop remedies that address the needs of communities now.

Mobilizing voters and demanding candidates speak about #BlackLivesMatter is basic. In municipal and county elections, virtually no one pays attention to the candidates for District Attorney or for Sheriff. It’s time to change that. While mayors, city council members, and county supervisors are supposed to represent their constituents, there are many in our communities who have more contact with the DA’s office and the county jail.

It’s also past high time to strengthen the authority of civilian police review boards, and to create them in places where they don’t exist. A review board, composed of local citizens, doesn’t have to rely on politically compromised prosecutors, and they can contest the results of internal reviews conducted by police departments. Review boards with subpoena and investigatory powers can dig up the truth and release their results to the public; unlike grand juries, they do not conduct their investigations in secret.

The idea of civilian police review boards was first proposed in the 1920s by civil libertarians concerned about the growing power of law enforcement. After the Harlem race riot of 1935, the mayor’s task force proposed a board for New York City, but Mayor LaGuardia rejected the idea as too radical. Washington, DC, set up the first official board in 1948; Philadelphia followed ten years later. Both boards reported their findings to the city’s police commissioner, but neither had the power to force changes in police practices.

Charges of police misconduct exploded during the civil rights movement and campus student protests. Citizens complained that the police acted like an occupying force in their neighborhoods. Indeed, the Kerner Commission concluded that almost every riot in the 1960s until March 1968 had arisen because of police brutality.

Citizens and government officials realized that police oversight agencies offered a useful channel for civilian anger. The Community Relations Service in the US Department of Justice recommends them as an intervention for addressing racial tensions with law enforcement.

In the 1960s, New York City Mayor John Lindsay set-up an effective board whose majority was non-police affiliated members. The NYPD immediately attacked it, sponsoring a municipal referendum that abolished it. (The city’s current Civilian Complaint Review Board just confirmed that NYPD officers continue to use chokeholds on suspects, and though they have been banned for years, the police department has “meted out little or no punishment.”) In 1973, Berkeley established a board with limited independent investigative authority. In 1974, after the acquittals of Detroit police officers who shot and killed three African American youths, voters created a board of police commissioners outside of the department which governed with its own civilian investigators and complaint review and reporting process. By 2000, more than a hundred agencies operated had review powers of police departments.

More recently, the Board of Alderman in Saint Louis, Missouri, has agreed on a measure to create a seven-member Civilian Oversight Board, though it will lack the legal authority that community members wanted because it will not have subpoena power and can only report its findings to the police officials. The US Justice Department began investigating “systemic misconduct and a lack of accountability” in Newark, New Jersey’s police department three years ago under then-Mayor Cory Booker. The new mayor, Ras Baraka, last month agreed to a federal monitor and proposed the creation of a nine-member civilian complaint review board, the first in the city’s history. Only one seat is designated for a former police officer. Black community leaders in St. Paul, Minnesota, just forced officials to agree to an outside audit of the city’s Police-Civilian Internal Affairs Review Commission; the Mayor denied the review was related to the shooting death of 24-year-old Marcus Golden by two police officers.

Police unions and police chiefs are opposed to strong civilian review, and boards have been plagued by police departments’ blatant refusals to cooperate when asked to submit evidence, or to assist in evaluating complaints. Civilians also complain when a board proceeds timidly. Trapped between community anger and police belligerence, boards without subpoena or oversight powers have a nearly impossible mission: they must maintain access to police records yet not offend the officers and supervisors who can accept or reject their recommendations.

Boards may not prevent more police brutality and abuse. In that sense, they may be as effective or ineffective as equipping officers with body cameras. But #BlackLivesMatter should support civilian review boards but only with independent authority to investigate complaints. Better yet, boards should have the power to recommend remedies directly to the mayor and city council members and not just to the police.

That, combined with different elected officials, might even lead to the prosecution of law enforcement officers who kill unarmed civilians.

(First posted for Beacon Broadside 2/11/15)

Selma, Black Leadership and Presidential Allies

Ana DuVernay’s movie Selma tells the inspirational story of a coalition of activists, young and old, students and ministers, local and national, radicals and “respectables” who, despite their differences came together three times in the spring of 1965 to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and confront state police intent on enforcing racial segregation. Viewers and reviewers want to know more about all the people surrounding Martin Luther King: King’s right hand in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference Ralph Abernathy and SNCC’s John Lewis. They want to know about the shooting death of Jimmie Lee Jackson by a state trooper as he was defending his mother from a police beating. People want to know about women in the movement, about Selma community organizer Amelia Boynton and the young girls who also took part.

So the recent flap over the role of President Lyndon Baines Johnson during this pivotal point of the civil rights movement distracts us not only from the historical truth, but does the further disservice by (once again) trying to make white people the center of the black freedom struggle. Joseph A. Califano, Jr. goes so far as to suggest that LBJ should be remembered as the “white savior” who suggested the march, rather than as a president who tried to stop it as the film portrays. (That dubious honor goes to John F. Kennedy who tried to shut down the 1963 March on Washington.)

President Johnson was neither the hero nor the villain; to characterize him as one or the other perpetuates the racial divisions that King and other anti-racists sought to overcome. The (white) historians interviewed about Johnson’s legacy failed to understand this as well. Johnson had more than three decades of decades of political experience and knew how pressure politics worked. He also supported the movement’s goals of first class citizenship and wanted Congress to pass a voting rights act. And this is where DuVernay misses an opportunity to teach audiences about the political value of protest and the power of the Oval Office.

Selma is of course a film, not a documentary. If viewers want the documentary, Henry Hampton’s magisterial 14-hour series Eyes on the Prize (1987) remains the definitive video; episode six, Bridge to Freedom examines the Selma march. But Hollywood likes to pair its heroes with villains, and depicting LBJ as the baddie was DuVernay’s narrative choice.

Yet in a time of dysfunctional politics and a pervasive belief that government can do nothing good, there were lessons about political strategy and the usefulness of allies that would have been phenomenal. Audiences could have seen a President who is pushed by protesters to use the national mood after Kennedy’s assassination to deploy his legislative moxie and the power of the office to do the morally right thing. We would not have a distracting debate over LBJ as a white savior, but a message about the critical value of political protest in pushing a progressive agenda through Congress.

Passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 required three separate but strategically-related actions. First, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that some of the practices used to deny suffrage were unconstitutional. In addition, the 24th Amendment, abolishing poll taxes, was finally ratified in 1964. Together, these created a legal framework for expanding and protecting citizens’ right to vote.

Rights on paper are not rights in practice. At the center of the struggle for voting rights were the African Americans and white supporters who fought, marched, went to jail and died. To be sure, segregationists’ brutal repression of the movement – and national television coverage of Bloody Sunday – resulted in broad public support for the protestors and their cause.

Pressure mounted on Congress to pass a federal voting rights bill. It was here that LBJ’s work as a movement ally was vital to winning bipartisan support. Johnson knew how to persuade reluctant and defiant Congressmen – many of them fellow Southern Democrats – and more critically, which members were vulnerable to White House pressure. As the long-time Senate majority leader, Johnson understood the legislative minefields he had traversed earlier when Congress passed the tepid Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first since Reconstruction. Johnson was up against die-hard segregationists, most of whom had signed the Southern Manifesto in 1956. Even so, at the signing ceremony for the Voting Rights Act in August 1965, President Johnson knew he was consigning the Democratic Party to years of defeat from white Southern voters.

History is complicated when told in full. With its many leaders and varied activists, Selma tells a magnificent story and the stories of African Americans’ struggle aren’t told often enough. The tale of LBJ and Congress is an inside-the-beltway anecdote and probably would have confused the movie’s narrative. But it would have given us an example of a President who was made to do the right thing.